Tom Ryalls is writer and producer of Can You See Into A Black Hole?, the second play of Iris Theatre’s 2021 Seed Commissions winners, originally commissioned by Upstart Theatre as part of DARE Festival 2018.

Tom Ryalls is a writer and producer whose work includes How to be an Astronaut (artsdepot – shortlisted for the Unlimited Emerging Artist Award). Their writing has been seen at Theatre Royal Stratford East, Theatre503, the Arcola Theatre, Slunglow and Shoreditch Town. They are also part of the SSE Creative Leadership programme funded by ACE and a trustee of the disabled commissioning organisation Unlimited.

Can You See Into A Black Hole? Is at Iris Theatre’s Summer Festival 28th June to 3rd July 2021. Tickets are on sale here.

Your new play ‘Can You See Into a Black Hole?’ is coming to Iris Theatre’s summer festival, what can you tell us about the play?

I think the word I’m using the most is “Epic”. The show really has a huge story at the heart of it, sure it’s about one family, but it’s also about these things that happen on a celestial scale like black holes. It’s about a boy that wants to be an astronaut, but then he has his first epileptic seizure and this thing he’s always wanted can’t be a reality anymore. The show is about him choosing a different adventure and going down a different path which might still take him to space, or at least bring space to him.

What inspired you to write it?

I had seizures for about 10 years, for me they only happened in my sleep and I don’t remember the seizures themselves. At first, without medication, I would stop breathing too. My entire life was shaped by something I could never remember and I really wanted to change that. So, when my dog Eric passed away when I was 23 it was a bit of a kickstart to interview my parents and I thought I was going to make a show which recreated the experience of those seizures, but in those conversations we found a different story.

Very few people talk about epilepsy, we don’t understand it very well, even doctors don’t have a great understanding of it. So, when you’re living with it, nobody teaches you to talk about in any way other than how to survive the seizures. My family got trapped in this, we didn’t have the conversations and we realised in these interviews, there was a whole story our family had never told.

So, I decided to tell it, I decided to tell the story of all the conversations we never had. This all sounds like a bit of a downer but that’s not what the show is like, it became something really joyful in response to this.

How do you think your experiences of working in the creative sector as a disabled artist has influenced your writing?

I think the main thing which has shaped my writing is my neurology. I have ADHD so if my writing can keep my attention, it can keep the attention of most people. A lot of the things I write have to be really imaginative, and have a big story, and move forwards with pace in order to keep me interested while writing. It means I struggle to write things which are slow or hyper-realistic, I enjoy have elements of magical realism in anything.

It’s sort of at odds with what commissioners expect from any writing who creates work about different kinds of marginalisation. We’re often expected to talk about the “gritty reality” of our lives, but I don’t think I owe people that, I think my imagination has more worth than my oppression.

What more needs to be done to ensure accessibility for all?

Lots of things needs to be done. Theatre is really allergic to any kind of plurality. We’re constantly trying to find the one thing we should do at the expense of other things. But, the only way we can make theatre more accessible is by doing lots of things at the same time. We need to change the buildings, we need to change how we make the work and what the works feels like at the end, we also need to change things outside the sector like the financial structures that support disabled people.

It’s a huge task, I’m not going to pretend it’s easy, but neither is producing a West End show and people do that all the time. We pick and choose what difficult things we do and we need to start choosing to break down the barriers we’ve built that stops disabled people being an integral part to theatre.

An easy start is to make sure that when decisions are being made – there is a paid disabled person present to voice concerns about how things are structured. Our director Deirdre McLaughlin has photosensitive epilepsy, she’s been triggered loads by unexpected flashing lights in shows. But, sensory input is one of the first things I think about when working on lighting.

What does it mean to you to be one of the 2021 seed commission winners, what opportunities has it given you?

It’s been great – having a central London platform you can invite press too is massive for me. We’re really obsessed as an industry with reviews, a lot of commissioners or development schemes would rather look at reviews than read your play, so I’m hoping this helps me break down this barrier as a writer.

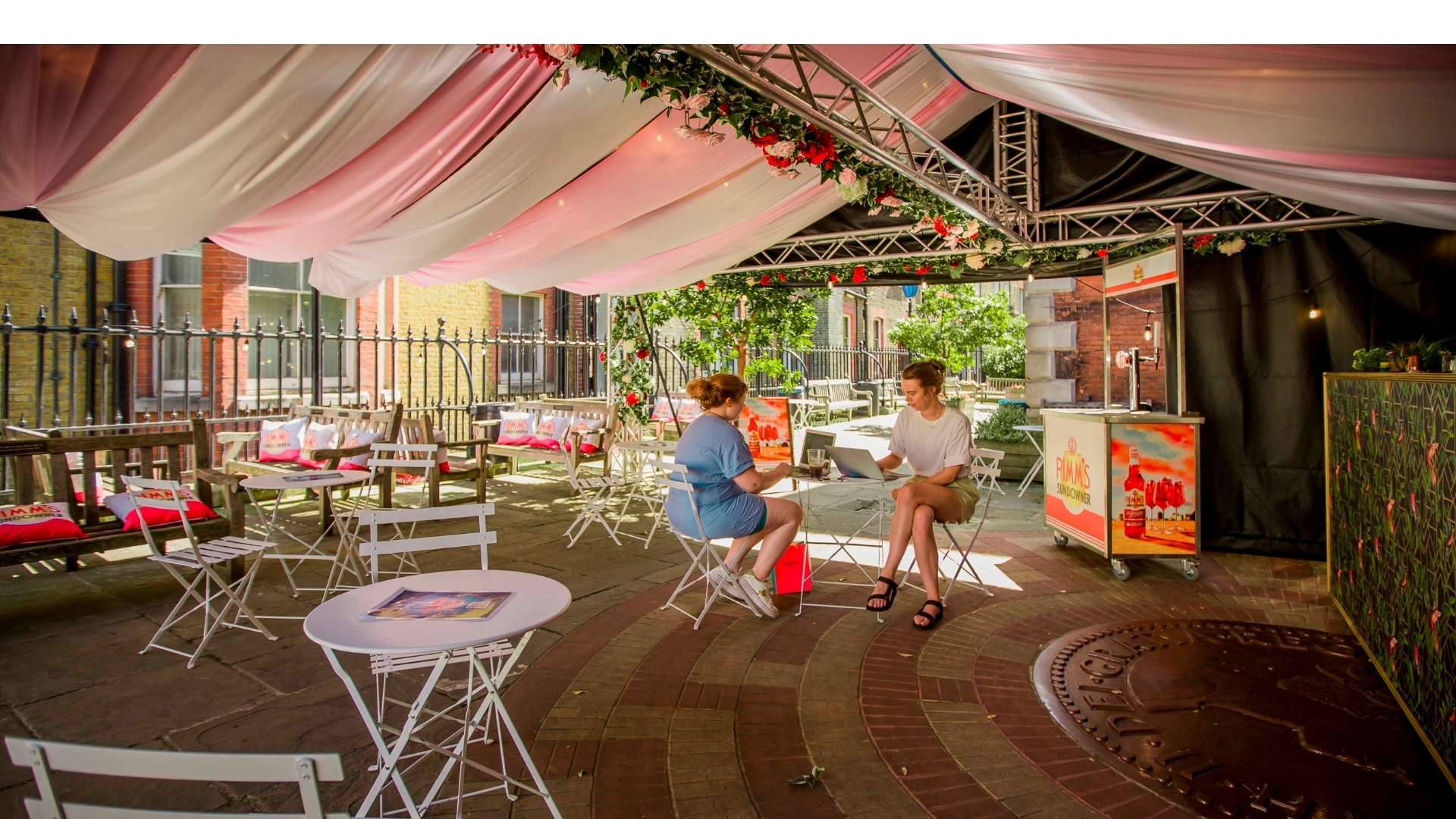

The theatre I make is relaxed-as-standard, it’s part of my craft, so I hope as well that being on this platform where we’re doing relaxed performances in the centre of Covent Garden makes it seem more possible in other Fringe or Off-Westend spaces too. Outdoor theatre itself is a huge opportunity for accessibility because you remove the need for stage lights which are the thing that creates most of the inaccessible sensory input.

What would you say to anyone thinking of coming to see ‘Can You See Into a Black Hole?’

The show has been crafted and developed over 3 years with a lot of love and lot of skills by a huge team – it’s bigger in ambition that I can probably describe and I hope you can see that. You can see a black hole while drinking wine in Covent Garden – what more could you want?