When Brian Friel’s Faith Healer, now regarded as one of the most important plays of all time, was first performed more than forty years ago, audiences were more accustomed to the kind of long form monologues that comprise this play. Now, in a revival at Lyric Hammersmith, modern audiences, used to the ‘quick fix’ of social media videos and streaming on demand, have to work almost as hard as the actors.

When Brian Friel’s Faith Healer, now regarded as one of the most important plays of all time, was first performed more than forty years ago, audiences were more accustomed to the kind of long form monologues that comprise this play. Now, in a revival at Lyric Hammersmith, modern audiences, used to the ‘quick fix’ of social media videos and streaming on demand, have to work almost as hard as the actors.

But for those willing to put in the effort, the end result of Rachel O’Riordan’s production is most definitely worth it. There are just three characters in this play; Francis ‘Frank’ Hardy, the titular Faith Healer, his wife Grace, and his manager, Teddy. They never interact with each other on stage, instead each delivering their own side of the story to the audience, one monologue per character except for Frank, who returns with a second and final story to tell.

Each are recounting episodes of the past; in the present Frank is already dead and the three of them have differing recollections of the events leading up to the night of his death.

In fact, they are all unreliable narrators; they tell us about their travels around Scotland and Wales in an old van, booking village and church halls for one night only so that Frank can ‘perform’. Friel’s script is deliberately vague around what Frank’s powers actually are, is it “a gift, a talent, or magic” wonders Grace. Frank admits himself that nine out of ten times he can’t heal anyone, yet there are examples of when he does achieve success, such as in Wales when ten people were cured in one night.

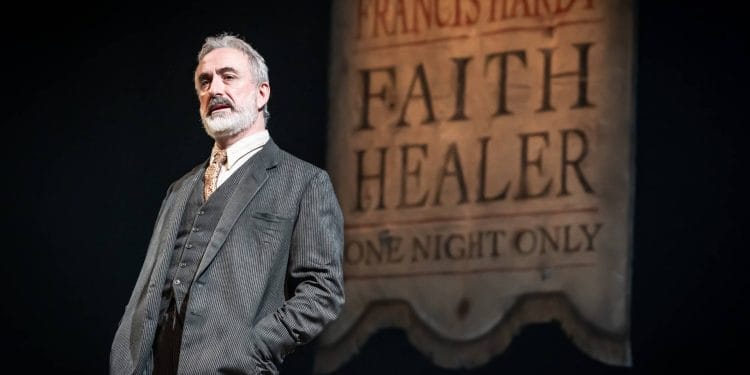

Declan Conlon is a smooth talker as Frank, giving the character the appearance of being suave and convivial while also being rough around the edges. Conlon’s first monologue is commanding and sets the scene for what’s to come.

Half the fun of this play is spotting the inconsistencies in the stories, next up is a captivating Justine Mitchell as Grace who tells a subtly different tale. It’s also here that we go beyond the world of Frank and start to understand the heartbreak and misery of those around him.

After the interval, there’s some much needed comic relief as the play temporarily shifts gear. In a powerhouse performance Nick Holder as Teddy regales us with stories of a bagpipe playing dog and a pigeon fancier. This, the longest of all the monologues, is not without it’s darker moments either, and again we find ourselves questioning which of the three, if any of them, are telling the truth about what really happened.

In an age of quick gratification Rachel O’Riordan focuses the attention of the audience completely on the speaker in front of them. There’s little in the way of set or props and Colin Richmond’s design evokes that sense of an empty village hall with rocky landscapes in the background.

At four decades old Friel’s play has earned its stripes. In this new production it feels fresh and revitalised. There’s no shying away from the fact that Faith Healer covers some big themes, from Irish culture to grief and abusive relationships, but it remains a masterpiece of storytelling.