It is hard to imagine that Noël Coward’s Fallen Angels was once considered scandalous. When it premiered in 1925, the notion of two respectable women openly discussing sex was enough to provoke outrage. A century later, the play feels more like a gentle comedy of manners, yet its wit and audacity still sparkle, proving Coward’s genius for turning social taboos into delicious farce.

It is hard to imagine that Noël Coward’s Fallen Angels was once considered scandalous. When it premiered in 1925, the notion of two respectable women openly discussing sex was enough to provoke outrage. A century later, the play feels more like a gentle comedy of manners, yet its wit and audacity still sparkle, proving Coward’s genius for turning social taboos into delicious farce.

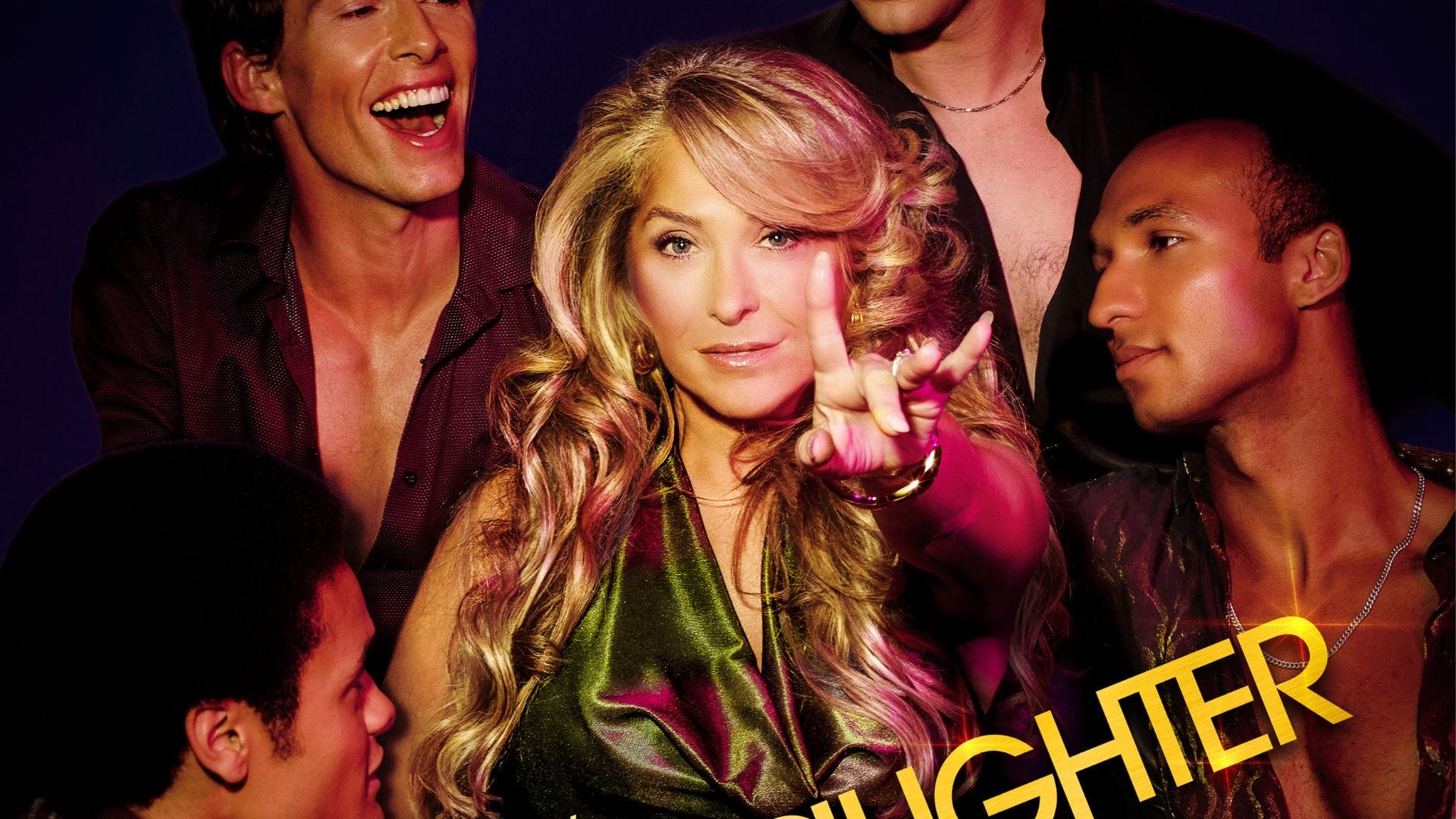

This revival, directed by Christopher Luscombe, marks the first London staging in 25 years. The plot is deceptively simple, Julia Steroll and Jane Banbury, two well-heeled golf widows, learn that Maurice Duclos, a former lover to both during a youthful Italian escapade, is back in London. His impending visit throws their comfortable marriages into chaos, testing friendship and fidelity in equal measure. What follows is a cocktail of anticipation, jealousy and temptation, shaken vigorously with Coward’s trademark repartee.

Simon Higlett’s set looks wonderfully authentic, evoking a chic 1920s apartment complete with a baby grand piano that becomes more than mere decoration. The design grounds the play in its era while allowing the comedy to breathe. Luscombe’s direction leans into the rhythm of Coward’s dialogue, ensuring the laughs come thick and fast, though Act Two’s dinner scene does sag slightly before regaining momentum as Julia and Jane descend into gloriously tipsy abandon.

The casting is impeccable. Janie Dee and Alexandra Gilbreath form a superb double act as Julia and Jane, their chemistry electric and their comic timing razor-sharp. Every raised eyebrow and conspiratorial glance lands perfectly, making their scenes together a joy to watch. Sarah Twomey is outstanding as Saunders, the maid whose competence and sly humour expose the pretensions of her employers. Her choreographed scene transition between acts is a highlight.

If the men feel somewhat sidelined, that is by design. Coward’s play, once criticised for its portrayal of women, now seems strikingly progressive. Julia, Jane and Saunders dominate the stage, driving the action while the husbands and Maurice appear in only the first and last scenes, giving the play a distinctly female centre. In this respect, Fallen Angels feels like it may actually have been ahead of its time.

There are moments where the pacing falters, but overall this is a stylish and spirited revival of a Coward classic that has been absent from London stages for far too long. Luscombe and his cast remind us why Fallen Angels remains one of Coward’s funniest creations: a play that once shocked society now simply delights it.

Listings and ticket information can be found here