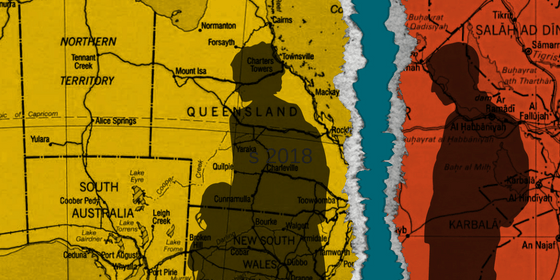

The world premiere of Louise Gooding’s Gold Coast, directed by Eloise Lally, begins promisingly enough. We look set to explore the trauma of war at a deep and meaningful level, with the consequences of the aftershocks fully laid bare. But, just like Saddam’s weapons of mass destruction, none of it actually materialises.

Joe, a soldier in the reserve army suffers some kind of trauma in the second Gulf War, which affects his relationship with his wife and daughter for many years to come. His father is also involved fleetingly, but given the play is marketed as being set across three generations, it is only really the character of Joe which has any meaningful emphasis placed upon it.

A barely intertwined plot line sees Joe’s daughter, Lisa, on the other side of the world, battling her own demons. One minute contemplating suicide in a chat room, the next taking money for a webcam striptease, it’s just about plausible, but the real problem is that the character is also played by Olivia Bromley, seen moments before cavorting with Joe as his wife. Through no fault of her own, Bromley simply doesn’t pass in any way as the thirteen-year-old girl, and any empathy you should feel for Lisa is lost in this distraction.

Too many scenes are frustratingly short, in the first ten minutes we spend more time watching the characters dash on and off stage, quickly resetting before engaging in another round of meaningless dialogue. Joe is determined not to reveal the cause of his trauma, which is mysterious at first, but soon becomes increasingly irritating.

The introduction of another new plot, and never before mentioned character, in the final ten minutes is perhaps supposed to answer some of our questions, but instead feels pointless and lazy. The doctor and healer characters are, I assume, supposed to be symbolic, but instead were completely out of place in the narrative. At least Tommy Burgess as Joe, gives Gold Coast something to be proud of. Buzzing with nervous energy, he does a good job of making the seemingly never-ending dialogue sound somewhat coherent.

Gold Coast spans three decades, but not in chronological order, a calendar on the wall keeps us abreast of the current date, but cannot make the time pass any more quickly for the audience. Much like Tony Blair and the Iraq War, writer Louise Gooding has thrown everything at Gold Coast, without sufficient reason. What could have worked as a shorter two-hander, is lost in a desert storm of unnecessary diatribes, clichés and complexity.