As far as comedians of the late 20th century go, Frankie Howerd earned the status of legend several times over; his career was often described as a series of comebacks. Like Larry Grayson, Kenneth Williams, and countless others, the public adored the campness of Howerd’s routines and lapped up every double entendre going. Mark Farrelly’s Howerd’s End, playing a short run at The Golden Goose Theatre, addresses a side of Howerd that the public didn’t see, and only properly became aware of following his death in 1992.

As far as comedians of the late 20th century go, Frankie Howerd earned the status of legend several times over; his career was often described as a series of comebacks. Like Larry Grayson, Kenneth Williams, and countless others, the public adored the campness of Howerd’s routines and lapped up every double entendre going. Mark Farrelly’s Howerd’s End, playing a short run at The Golden Goose Theatre, addresses a side of Howerd that the public didn’t see, and only properly became aware of following his death in 1992.

While camp comedians were very much in vogue, homosexuality was not. For much of Howerd’s younger life, a relationship with another man would have meant prison, he was also deeply ashamed of his sexuality and kept it secret from the public as well as his own mother. Also needing to be kept hidden was his long term partner, Dennis Heymer, often described as a friend, manager, chauffeur, or sometimes “just a nobody.”

Heymer outlived Howerd, and would remain living in their Somerset Home, Wavering Down, for another seventeen years, using that time to meticulously curate Howerd’s memorabilia and inviting tour parties of fans to view the house. As the audience for Farrelly’s play, we become the last ever party to visit Wavering Down, and the first to hear the story of the couple’s life together from Heymer’s point of view.

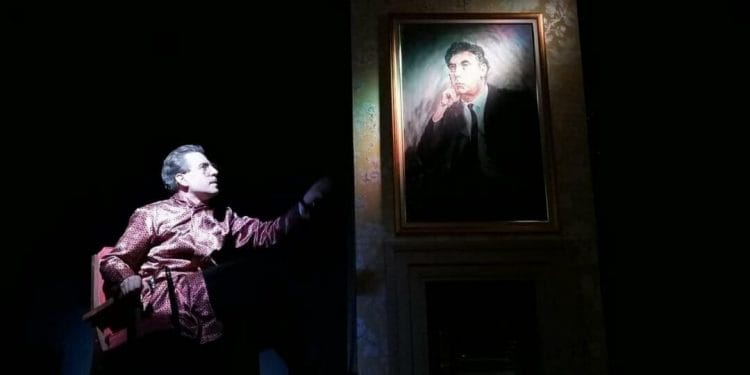

It’s a ghostly apparition above the three-bar electric fire that prompts Dennis Heymer, played by playwright Mark Farrelly, to begin the story. Joined on stage by Frankie himself, returned from the dead to support Dennis every step of the way. A wave of the hands and we’re transported back to 1959, when Dennis was a Sommelier at the Dorchester and Howerd, lunching with John Gielgud, caught his eye.

The play jumps around several key milestones in the couple’s relationship, but constantly reminds us that they lived their lives shrouded in secrecy. Howerd’s End frequently breaks the fourth wall, just as Frankie would frequently do in real life with seemingly unscripted asides. While this story belongs to Dennis, Frankie is undeniably at the centre of it, but the script quite cleverly draws attention to elements of Howerd’s life without feeling the need to explain them in detail; his crippling stage fright is covered in just a few lines.

So Heymer does get to tell his story, but only to the point where we realise that one would probably not exist without the other. Farrelly clearly knows his stuff, the writing of Howerd is superb, allowing the “oooh’s” and “titter ye not’s” to have their place, but still allowing us to see the introverted and frightened man that existed off stage. His performance as Dennis is equally as strong, easily transitioning from a frail 80 year old to a confident 30 year old back at the Dorchester.

Simon Cartwright, who recently portrayed Bob Monkhouse on stage, has captured the voice and mannerisms of Howerd perfectly, even if some of the facial expressions and body movements don’t feel entirely natural.

One or two scenes linger on a little too long, but in general the transitions to different times and places, coupled with the frequent asides is enough to keep the audience engaged. While Frankie Howerd looms large in this production, it is Farrelly’s writing and portrayal of Dennis Heymer that makes Howerd’s End stand out as a witty and insightful piece of drama. For all their ups and downs, the pair clearly loved each other, and Farrelly’s love of his subject matter is clear to see.