Peter Mottley’s After Agincourt is a sequel monologue by Pistol—the last surviving character of the Boar’s Head Tavern gang. It ruthlessly examines a darker side of this little world which was once raucously filled with laughter and booze, but eventually abandoned by the newly crowned Prince Hal. The script picks up in the aftermath of the famous Agincourt Battle where Pistol (Gareth David-Lloyd) painfully reckons the loss of Bardolph, Nym, Falstaff, Mistress Quickly, and the Boy. No more jests and japes; this is a Pistol traumatised and haunted by war and his own ghostly weight of survival.

Peter Mottley’s After Agincourt is a sequel monologue by Pistol—the last surviving character of the Boar’s Head Tavern gang. It ruthlessly examines a darker side of this little world which was once raucously filled with laughter and booze, but eventually abandoned by the newly crowned Prince Hal. The script picks up in the aftermath of the famous Agincourt Battle where Pistol (Gareth David-Lloyd) painfully reckons the loss of Bardolph, Nym, Falstaff, Mistress Quickly, and the Boy. No more jests and japes; this is a Pistol traumatised and haunted by war and his own ghostly weight of survival.

One may regard After Agincourt as an extension of Falstaff’s iconic “honour speech,” sharpened into a critique of the vanity of glory. It is deeply anti-heroic and intrinsically anti-war: he constantly returns to the image of “boys and luggage,” unable to let them go even after Henry’s vengeance on the prisoners, or, in this writing, especially after Henry’s vengeance. He points out that even if revenge is executed in their name, the boys will never return. David-Lloyd’s portrayal feels not only venerable and emotionally wrenching but also, in ways, bracingly modern, echoing Shakespeare’s own later-career shift where he turned away from cycles of vengeance toward the notion of forgiveness.

Mottley also dares to speak against the towering shadow of the St Crispin’s Day speech. So often performed with triumphalist and patriotic fervour, such as by Olivier in wartime Britain and by Branagh with bloodied valour in 1989, Mottley’s counterpoint eerily resonates with Mark Rylance’s more melancholic reading: self-effacing, fatigued, half-convinced by its own courage. Rylance’s Henry, performed almost 30 years ago, was almost a reluctant boy-king, fragile and evasive, forcing himself to comfort his fellow Englishmen. There’s something of that quality in Mottley’s Pistol as well—a nuanced sadness gently wrapping his deeply humane concerns.

However, the writing is not without flaws. At times, this overtly scathing Pistol feels less like the character we know and more like a mouthpiece. As a one-hander, the intimacy should have heightened audience engagement, but the writing’s lack of humour distances the audience rather than drawing them in. Shakespeare’s Pistol is hollow and cowardly, but his misquotes and parodies always make us laugh. Here, only an occasional flicker of humour breaks through its intensity. If the script can better balance its comic rhythm—as well as better engagement with the audience—and its emotional and psychological weight, the interplay may better allow Pistol to live more fully as Shakespeare’s larger-than-life canon.

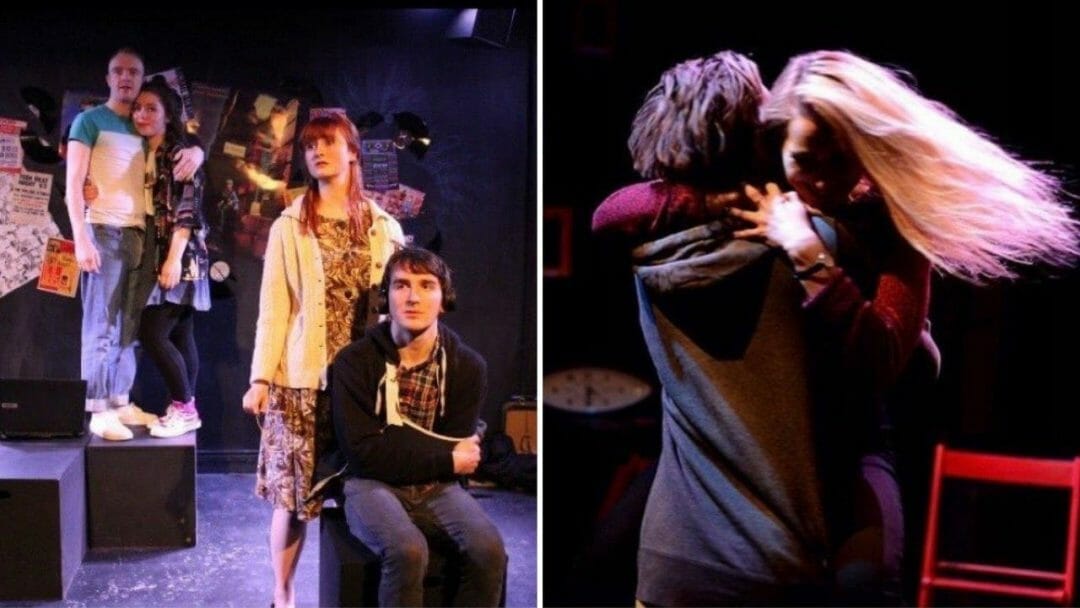

Visually, the set is sparse but effective. A rustic wooden table and stool provide a focal point that underscores Pistol’s immense loneliness. The lighting design (by Venus Raven) lessens clarity in transitions, yet not to an extent that diminishes the overall smoothness. Director Paul Olding always keeps David-Lloyd in motion, whose portrayal of Pistol is at the same time extremely explosive yet manoeuvres with the most precise self-control: a Pistol drunk on memory but terrifyingly sober about his world. Shakespearean in force, his Pistol mocks the archers in the battlefield—and David-Lloyd himself is such an archer, shooting his lines with emotional ebbs and flows at us.

After Agincourt is unafraid to wound the myths of patriotism and glory of Shakespeare’s Henries. Though it might be hampered by its writing arrangements and design choices, it certainly bears clear potential to grow into something that can fully capture and expand the bitter, sharp, but deeply humane questioning embedded in Shakespeare’s text.