Created by celebrated television producer and writer Dan Patterson, of Whose Line Is It Anyway? and Mock the Week fame, and diplomat-meets-mediator Daniel Taub, whose skills in negotiating have taken him to the Middle East as well as universities, research commissions and foreign ministries around the world, Winner’s Curse is set up for success. It promises to be a night of witty yet tense debate and interactive revelation helmed by its star: broadcaster and presenter Clive Anderson. Disappointingly, what results is anything but.

Created by celebrated television producer and writer Dan Patterson, of Whose Line Is It Anyway? and Mock the Week fame, and diplomat-meets-mediator Daniel Taub, whose skills in negotiating have taken him to the Middle East as well as universities, research commissions and foreign ministries around the world, Winner’s Curse is set up for success. It promises to be a night of witty yet tense debate and interactive revelation helmed by its star: broadcaster and presenter Clive Anderson. Disappointingly, what results is anything but.

The show opens as our narrator Hugo Leitski (Clive Anderson) celebrates a lifetime dedicated to delegation by accepting a prestigious award. However, as the show goes on and Hugo’s skills are revealed to be nothing but trite and simplistic card tricks, we’re left puzzled as to how he even managed to be recognised for his work.

Though Anderson’s charm is undeniable, his attempts to motivate the audience to learn about the art of negotiation are set up for failure since the script only ever wades very shallowly into the subject through gimmicky and predictable exercises such as one-step wagers and thumb wars.

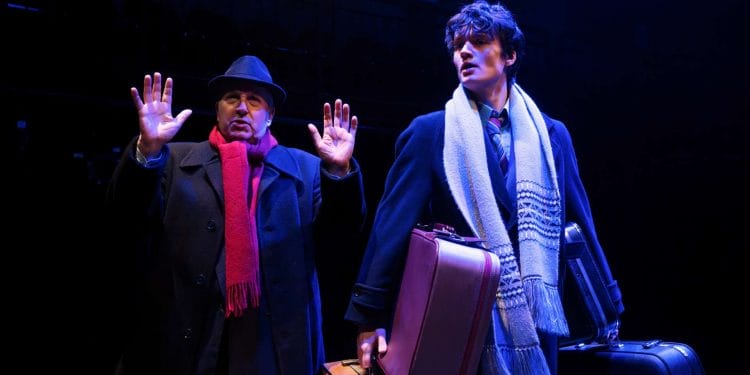

Even the show’s second narrative, set decades prior in Hugo’s early adulthood, flounders to make a point. It expands on the show’s cast of characters, yet never renders them in all their dimensions, leaving them flat and uninspired.

The comedic tensions inherent to diplomacy go largely unexplored, replaced by the slapstick comedy of a cringe-worthy American negotiator named Tyler (Greg Lockett) and a zany hotel operator named Vaslika Krenskaya (Nichola McAuliffe), albeit the latter being an enviable character for any character actor and surely a joy to play. Generally, the show’s humour would have succeeded more had it not been so aware of its attempted effect; audiences rarely want to be spoon-fed a joke.

Unfortunately, the show’s glib writing extends beyond its humour, proving transparent at the best of times and superficial at the worst. Though its pacing is efficient and well-measured (combining two narratives and consistent wall-breaking), the writing’s incorporation of diplomacy, comedy, and sincerity was more often than not quite unsubtle and contrived.

Its wordplay quickly got tiring and its plot was somehow still too linear despite being scattered between timelines. The show’s interactive elements were pedantic, underdeveloped, and offered no new insights into the skills required to efficiently negotiate.

Clive Anderson’s Hugo is sympathetic, if only for his own bumbling nature. Yet, there is only so long you can chalk Anderson’s floundering up to his charm. From stumbling over his lines to barely controlling the audience during the show’s interactive intervals, Anderson made the performativity of the show impossible to forget.

Due to the show’s intentional incorporation of the audience, this isn’t an issue per say. However, the show’s messy execution can’t be written off as a choice. Whether over or under-rehearsed, Winner’s Curse can’t quite shake the effects of its own mediocrity.

Winner’s Curse is playing at London’s Park Theatre until March 11th.